The CTO’s Double Diamond

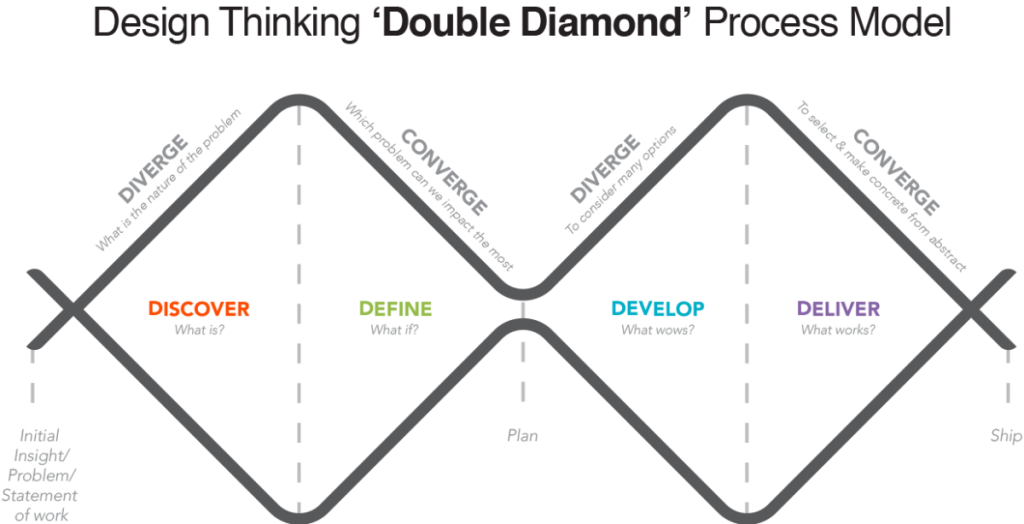

A two-diamond design model that aligns engineering and product teams through divergence and convergence across four phases: Discover, Define, Develop, and Deliver.

I’m sitting in our weekly product-engineering sync, and the tension is thick enough to cut with a keyboard. Our product manager is presenting wireframes for a “simple” customer dashboard. She’s excited, animated even, walking through user journeys and engagement metrics. Meanwhile, my senior engineers are exchanging those looks—the ones that scream “she has no idea what she’s asking for.”

“This should take, what, two sprints?” the PM suggests optimistically.

My lead engineer’s coffee mug pauses halfway to his mouth. “Try two quarters,” he mutters, just loud enough for everyone to hear.

The zoom call descends into chaos. Product accuses engineering of sandbagging. Engineering accuses product of living in fantasy land. I’m caught in the middle, watching months of carefully built trust evaporate in real-time. We’re supposed to be one team, building one product, but we might as well be speaking Klingon and Elvish to each other.

The meeting ends with nothing resolved. The PM no doubt headed to “escalate matters to the CEO.” My engineers retreat to Slack to vent about “impossible requirements.” And I’m left staring at an empty zoom call, wondering how we got here.

Three months later, this same team is shipping features faster than ever, with product and engineering finishing each other’s sentences. The transformation didn’t come from better project management tools or more detailed specs. It came from stealing a design framework that most CTOs have never heard of—the Double Diamond.

Author’s note: I do want to thank Allan Stewart for introducing me to this concept.

The Core Idea

The Double Diamond isn’t just a design process—it’s a universal framework for navigating complexity that transforms how CTOs orchestrate the dance between discovery and delivery, between possibility and pragmatism.

Two Diamonds Are Better Than One Waterfall

The Double Diamond was popularized by the British Design Council in 2005, adapted from the divergence-convergence model proposed in 1996 by Hungarian-American linguist Béla H. Bánáthy. The framework splits problem-solving into four distinct phases: Discover, Define, Develop, and Deliver. Two diamonds, each representing a cycle of divergent thinking (exploring possibilities) followed by convergent thinking (making decisions).

Most CTOs know this pattern intimately, even if they’ve never seen it drawn. We diverge when we explore different architectures. We converge when we choose our tech stack. We diverge when we investigate performance bottlenecks. We converge when we implement the fix.

But something magical happens when you make this implicit pattern explicit and apply it to the product-engineering divide.

According to the Design Management Institute, design-driven companies outperformed the S&P 500 by 219% over a 10-year period from 2004-2014. Yet most CTOs treat design frameworks as “product team stuff,” missing the profound implications for technical leadership.

The first diamond (Discover → Define) is about understanding the right problem. The second diamond (Develop → Deliver) is about building the right solution. Simple concept. Revolutionary application.

The Problem Diamond: Where CTOs Usually Fail

Most CTOs jump straight to the second diamond. We’re solution machines. Give us a problem, and we’ll architect an answer before you finish explaining the question. It’s our superpower and our kryptonite.

In my case, every product-engineering clash traced back to the same root cause: we were skipping the first diamond entirely. Product would show up with solutions (wireframes, specs, user stories), and engineering would immediately start solutioning on top of their solutions. We were trying to converge without ever diverging.

The Discover phase isn’t about gathering requirements. It is about understanding the problem space. When my team started spending two days per feature just exploring the problem (not the solution), everything shifted. Engineers interviewed customers directly. Product managers dove into system logs. We diverged consciously, documenting what we didn’t know rather than pretending we had all the answers.

While the famous “100x cost” statistic about fixing bugs in production versus design has been widely cited, investigation has shown the original IBM Systems Sciences Institute study doesn’t actually exist. However, the principle remains valid: research from multiple sources consistently shows that fixing problems in production costs significantly more than addressing them during design, with estimates ranging from 10x to 100x the cost.

The Define phase is where you converge on what problem you’re actually solving. Not the feature request. Not the user story. The actual problem. This is where my team developed our “Problem Brief”—a one-page document that everyone, from junior developer to CEO, had to agree on before any solution discussion began.

One brief from that era: “Customer Success spends 4 hours daily manually correlating data across three systems to identify at-risk accounts, resulting in 48-hour delay in intervention and 20% higher churn for unidentified accounts.” No solutions. No features. Just the problem, the cost, and the impact.

The Solution Diamond: Where Engineering Shines

Once you’ve defined the right problem, the second diamond becomes pure joy for engineering teams. The Develop phase is where we diverge again, but now we’re exploring solutions to a well-understood problem.

This is where your architects earn their equity. Multiple approaches, different trade-offs, various technologies all explored with the confidence that you’re solving the right problem. We started using a simple matrix: Technical Complexity vs. Business Impact. Every solution option got plotted. The conversations became about trade-offs, not opinions.

During one Develop phase, we explored five different approaches to that customer success problem:

Full data warehouse implementation (high complexity, high impact)

Automated daily reports (low complexity, medium impact)

Real-time streaming pipeline (high complexity, high impact)

Manual SQL queries with documentation (minimal complexity, low impact)

Third-party integration platform (medium complexity, medium impact)

The Deliver phase is where most CTOs think they spend all their time, but if you’ve done the first three phases right, delivery becomes almost anticlimactic. The arguments are over. The trade-offs are understood. The team is aligned.

We chose the automated daily reports as our MVP, with a clear path to the streaming pipeline. Product understood why. Engineering understood the business value. Customer Success understood the timeline. Six weeks later, we’d reduced their daily work from 4 hours to 30 minutes.

Real Companies, Real Results

The British Design Council’s original research studied 11 global companies including Apple, LEGO, Microsoft, Sony, and Starbucks, finding that they all naturally followed this same creative process despite having different names for it.

Starbucks even mandates that any designer spend a month working as a barista in their stores to truly understand the discovery phase.

More recent implementations show impressive results. Artkai, a design agency, used the Double Diamond framework for CoinLoan’s P2P lending platform, resulting in over 100,000 active users. They also applied it to Huobi’s mobile trading platform expansion into Europe, successfully adapting the product for a new market by studying European user needs and creating features that differentiated it from competitors.

Companies like IDEO, Google, and Microsoft have integrated Double Diamond principles into their innovation and product development processes, with Google’s design sprints reflecting the framework’s emphasis on deep problem understanding and iterative solution development.

The Rhythm of Diamonds

The revolution isn’t in using the Double Diamond once—it’s in making it your operating rhythm. Every feature, every quarter, every technical decision flows through these diamonds.

We established a cadence:

Week 1-2: Discover (diverge on problem understanding)

Week 3: Define (converge on problem definition)

Week 4-5: Develop (diverge on solution options)

Week 6: Deliver planning (converge on solution approach)

Week 7+: Implementation

For smaller problems, we’d run through both diamonds in a single week. For major initiatives, each phase might take a month. The framework scales.

McKinsey research on decision-making shows that organizations following structured approaches that separate problem definition from solution development make faster decisions with better outcomes, with speed and quality reinforcing rather than undermining each other. The Double Diamond isn’t slowing you down but rather it is preventing the three rewrites that happen when you solve the wrong problem brilliantly.

The Organizational Transformation

Six months into our Double Diamond journey, the transformation was undeniable. But it wasn’t just about shipping better features faster (though we were). The real change was cultural.

Engineers stopped complaining about “stupid product decisions” because they were part of problem discovery. Product managers stopped accusing engineering of “technical excuses” because they understood the solution trade-offs. The CEO stopped getting escalations because problems were being solved at the team level.

Our metrics told the story:

Feature delivery time: decreased 40%

Post-launch bugs: decreased 60%

Team satisfaction scores: increased from 6.2 to 8.4

Customer feature adoption: increased 35%

But the metric that mattered most? The number of “emergency pivot” meetings dropped to zero. When you understand the problem deeply and explore solutions thoughtfully, surprises disappear.

Implementation Without Revolution

You don’t need to reorganize your entire company to start using the Double Diamond. Start with one team, one feature, one experiment.

Pick your most contentious upcoming feature—the one where product and engineering are already at odds. Block one day for problem discovery. Not solution discovery. Problem discovery. Get everyone in a room: engineering, product, sales, customer success, even a customer if you can.

Draw two diamonds on the whiteboard. Explain the phases. Then start with this question: “What problem are we trying to solve, and how do we know it’s a problem?”

Watch what happens when your senior engineer realizes the performance issue they’re worried about doesn’t actually impact the user workflow. Watch your product manager’s face when they understand the technical debt that makes their “simple” request complex. Watch the magic when everyone converges on a problem definition that makes sense to all.

Document everything in a Problem Brief:

The problem (one sentence)

Who experiences it (specific users/personas)

When they experience it (context/triggers)

Cost of not solving it (time/money/satisfaction)

How we’ll measure success (specific metrics)

No solutions allowed in this document. That’s for the second diamond.

For the solution diamond, create a Solution Matrix:

Option name

Technical complexity (1-5)

Business impact (1-5)

Time to implement (weeks)

Risks and dependencies

Long-term implications

Plot these on a 2x2 grid. Let the trade-offs become visible. Make the decision together.

The CTO’s New Superpower

The Double Diamond transforms the CTO from a technical decision-maker into an orchestrator of understanding. You’re no longer the bridge between product and engineering. You’re the conductor ensuring everyone plays the same symphony.

This framework gives you a language for the C-suite that isn’t about story points or technical debt. You can walk into the board room and say, “We spent two weeks in problem discovery and identified that what looked like a product issue was actually an infrastructure bottleneck costing us $200K monthly. The solution will take six weeks and pay for itself in three months.”

That’s a conversation every CEO wants to have.

More importantly, it gives your team a way to handle complexity without you. When everyone understands the Double Diamond, they can run it themselves. Your senior engineers start thinking like product managers. Your product managers start thinking like engineers. And you get to focus on strategy instead of refereeing.

Monday Morning Actions

This Monday, do three things:

First, draw the Double Diamond for your leadership team. Explain that every significant decision will now flow through these four phases. Watch for resistance. It usually comes from people who pride themselves on “quick decision-making” but actually create more chaos than progress.

Second, identify three current conflicts between product and engineering. Map them to the Double Diamond. I guarantee you’ll find they’re all stuck because you’re in different phases. Usually product is in Deliver while engineering is still in Discover.

Third, block time for problem discovery. Real time. Sacred time. This Friday, 2-4 PM, entire team, no solutions allowed. Just understanding the problem. Make it a recurring meeting.

Within a month, you’ll see the shift. The heated debates become structured discussions. The us-versus-them mentality dissolves into shared understanding. The delivery velocity increases not because people type faster, but because they’re building the right thing the first time.

Within a quarter, your team will internalize the rhythm. They’ll start asking, “Are we in divergent or convergent thinking?” They’ll catch themselves jumping to solutions and pull back to understand the problem first.

Within a year, you’ll wonder how you ever operated differently. The Double Diamond won’t be a process you follow, it’ll be how your organization thinks.

The distance between product and engineering isn’t measured in sprints or story points. It’s measured in understanding. The Double Diamond doesn’t just bridge that gap. It eliminates it entirely.

Your next product-engineering sync doesn’t have to be a battlefield. It can be a design studio where problems are understood and solutions are crafted collaboratively. All it takes is two diamonds and the discipline to work through both of them.

The question isn’t whether you can afford to spend time in problem discovery. The question is whether you can afford not to. Every minute spent in the first diamond saves hours in the second. Every divergent conversation prevents a convergent crisis.

Welcome to the Double Diamond. Your team will thank you. Your CEO will thank you. And most importantly, your customers will thank you. Not with words, but with adoption, retention, and revenue.

Thanks for writing this, it clarifes a lot. This insight into team friction is super valuable, much like your other pieces.

While I have approached problems in a similar fashion, I didn’t have this framework at hand. Totally makes sense how this can resolve problems and get everyone aligned. So true that engineering tends to start at the second diamond while product is still in 1. Thank you for sharing.