The CTO’s Methodological Pivot

How AI is forcing CTOs to rethink everything they believed about Agile and Waterfall

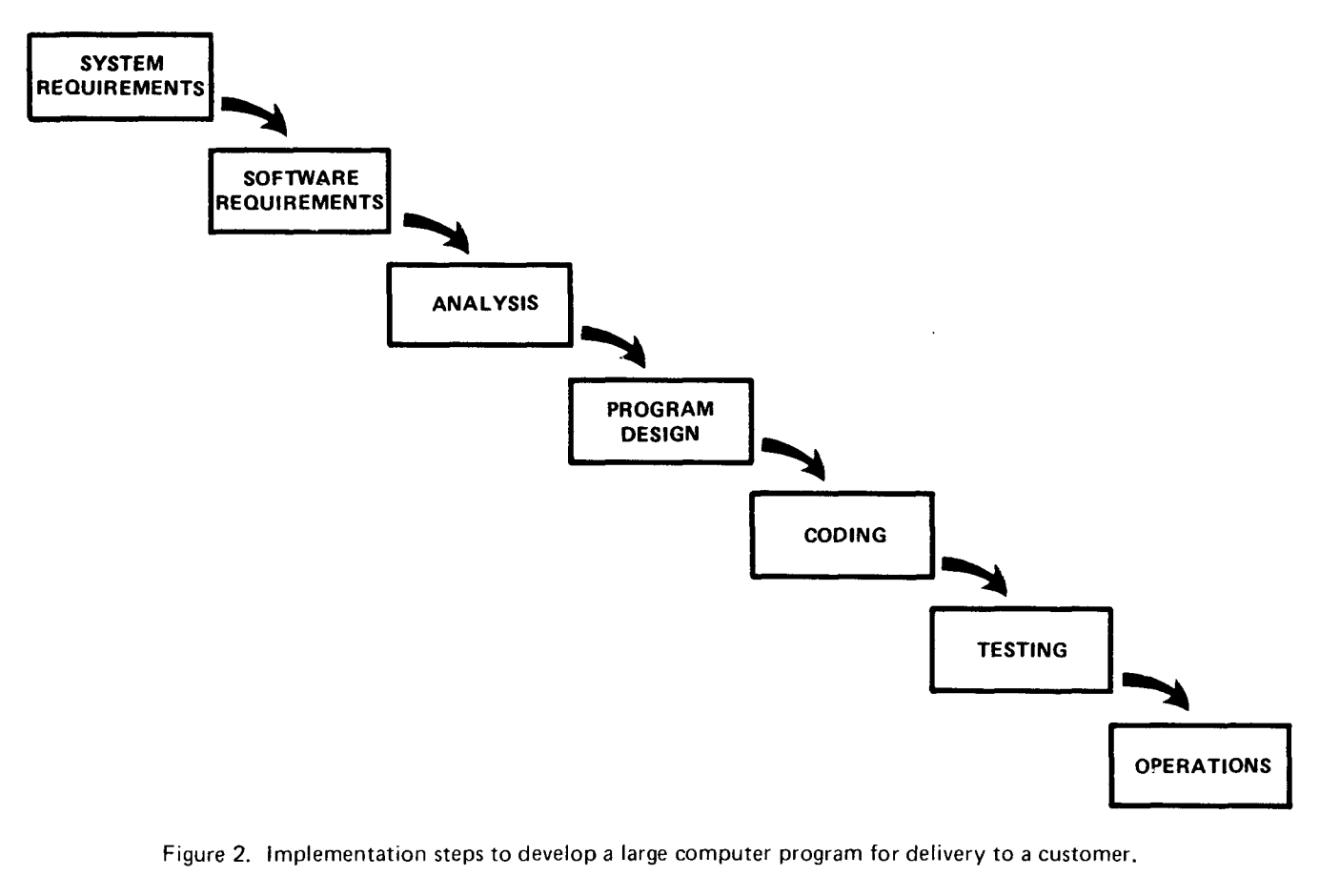

In August 1970, Winston Royce stood before an audience at IEEE WESCON and presented a paper that would be misquoted for the next fifty years. His eleven-page document, “Managing the Development of Large Software Systems,” contained a diagram showing a sequential flow from requirements to operations. That diagram, later dubbed “waterfall,” became the poster child for rigid, phase-gated development.

Royce never used the word waterfall. More importantly, directly beneath his now-infamous diagram, he wrote something the industry conveniently ignored: “I believe in this concept, but the implementation described above is risky and invites failure.”

The man credited with inventing waterfall was actually warning against it.

Royce spent the remainder of his paper advocating for iteration, prototyping, and feedback loops. His third recommendation was explicit: “Do it twice.” Build a pilot model first—what he called a “simulation”—to test critical design and operational areas before committing to the version delivered to the customer. He described the unique skills needed for this pilot phase: developers who “must have an intuitive feel for analysis, coding and program design” and can “quickly sense the trouble spots in the design, model them, model their alternatives.” His son, Walker Royce, would later become a principal contributor to the IBM Rational Unified Process, an iterative methodology. The irony is complete.

Three Decades of Monuments to a Misreading

For three decades, software teams built monuments to a misreading. Requirements documents grew to hundreds of pages. Sign-offs multiplied. Testing became something that happened after all the code was written, right before the panicked realization that nothing worked as expected. Projects hemorrhaged money, missed deadlines, and delivered systems nobody wanted.

The industry was ready for a rebellion.

Seventeen Anarchists in the Mountains

On February 11, 2001, seventeen software practitioners drove up Little Cottonwood Canyon to the Lodge at Snowbird in Utah (I just moved here btw!!). They represented competing methodologies with names like Extreme Programming, Scrum, Crystal, and Dynamic Systems Development Method. Bob Martin, who organized the gathering, later joked that assembling a bigger group of organizational anarchists would be hard to find.

They came because the status quo had become unbearable. The average lag between identifying a business need and deploying a software solution had stretched to three years. Documentation had replaced delivery. Process had suffocated progress.

What They Agreed On

Martin Fowler, one of the attendees, expected little from the meeting beyond making contacts that might turn into “something interesting.” Alistair Cockburn had reservations about the term “lightweight methodologists” that the group had been using: “I don’t mind the methodology being called light in weight, but I’m not sure I want to be referred to as a lightweight.”

What emerged from those two days surprised everyone, including the participants. They agreed on four values and twelve principles that prioritized working software over comprehensive documentation, customer collaboration over contract negotiation, and responding to change over following a plan.

The only concern with their chosen name came from Martin Fowler, who worried that most Americans didn’t know how to pronounce the word “agile.”

The Manifesto’s Unintended Reach

The Manifesto spread faster than any of its authors anticipated. Mike Beedle, one of the signatories, never foresaw its adoption in contexts beyond software, like leadership and sales. James Grenning took years to realize it was “such a big deal.” Kent Beck’s original vision for Extreme Programming was simply to make the world safe for programmers.

For two decades, Agile became orthodoxy. Sprints replaced phases. User stories replaced requirements documents. Standups replaced status meetings. The pendulum had swung.

The Core Idea

The methodology that wins is the one that matches how you actually build.

Waterfall failed because it assumed requirements could be known completely upfront. Agile succeeded because it embraced uncertainty. Now AI is introducing a third variable: when your implementer is an algorithm, the rules change again.

Why This Matters Now

Something unexpected is happening in engineering organizations that have embraced AI coding assistants. Teams are writing more documentation, not less. Design documents are growing longer. Requirements specifications are becoming exhaustive. One engineering leader described the emerging pattern as “Agile planning, waterfall execution.”

The reason is straightforward: AI thrives on precision. As one AI engineer put it, “the agents we have right now need what waterfall provides even more than people do.”

The High Cost of AI Coding

When you hand a vague prompt to Claude or Copilot, you get vague results. The AI will happily generate plausible code, but plausible isn’t the same as correct. The model makes assumptions at every turn. Sometimes those assumptions align with your intent. Often they don’t. You end up in a debugging loop that feels less like pair programming and more like archaeology.

Andrej Karpathy, co-founder of OpenAI, coined the term “vibe coding” in February 2025 to describe this loose approach: describing what you want in natural language, accepting AI suggestions without carefully reading the diffs, and iterating until something seems to work. It’s fast. It’s fun. And according to a randomized controlled trial published by METR in July 2025, experienced open-source developers using this approach on their own mature codebases actually took 19% longer to complete tasks than those working without AI assistance.

The METR Study: What CTOs Need to Know

The study deserves a closer look. METR recruited 16 developers who had contributed to large open-source repositories (averaging over one million lines of code and 22,000 GitHub stars) for an average of five years. These weren’t beginners learning a new codebase. These were experts on home turf, using frontier tools like Cursor Pro with Claude 3.5 and 3.7 Sonnet during the February-June 2025 study period.

The perception gap was striking. Before starting, developers predicted AI would make them 24% faster. After completing the study, they estimated AI had improved their productivity by 20%. The actual measurement: 19% slower. METR explicitly notes that their results may not generalize to other contexts—less experienced developers, unfamiliar codebases, or different types of tasks might see different outcomes. But for experts working on systems they know intimately, the vibe coding approach created more friction than it removed.

The problem isn’t the AI. The problem is the input.

The Distinction That Matters

Simon Willison, a programmer who has thought deeply about AI-assisted development, draws a clear line: “If an LLM wrote every line of your code, but you’ve reviewed, tested, and understood it all, that’s not vibe coding. That’s using an LLM as a typing assistant.” The distinction matters because it identifies where the value creation actually happens.

Amazon’s Kiro, an agentic IDE launched in July 2025 and made generally available in November, embodies this insight. When you start a new project in Kiro, it asks you to choose between two modes: “Vibe” for exploratory chat-driven coding, or “Spec” for plan-first development. The Spec mode forces you through a structured workflow: first, requirements with detailed acceptance criteria written in EARS notation; then, technical design with diagrams and schemas; finally, implementation tasks sequenced by dependency.

Why AWS Built a Project Manager Into an IDE

AWS’s rationale was blunt. As product lead Nikhil Swaminathan and VP Deepak Singh explained: “When implementing a task with vibe coding, it’s difficult to keep track of all the decisions that were made along the way, and document them for your team.” The spec-driven approach emerged because users weren’t giving AI enough detail to get high-quality results. The tool itself acts like a project manager, guiding teams to plan before coding.

Research cited by AWS found that addressing issues during the planning phase costs five to seven times less than fixing them during development. This principle has always been true. What’s changed is that AI agents amplify the difference. A human developer encountering an ambiguous requirement might pause, walk over to a product manager’s desk, and ask a clarifying question. An AI agent encountering the same ambiguity will make a decision and keep generating code.

We’ve Heard This Before

If you’re experiencing déjà vu, you’re not wrong. “The spec is the code” echoes promises from the 1990s—UML, Model-Driven Architecture, CASE tools that would let us draw diagrams and generate applications. Those initiatives failed because the visual specifications became as complex as the code they were supposed to replace. The abstraction didn’t abstract; it just moved the complexity sideways.

LLMs are different in one important respect: they handle natural language ambiguity far better than the rigid schema-driven tools of that era. A CASE tool choked on anything outside its formal grammar. An LLM can interpret “make the button look clickable” and produce reasonable CSS, even though that phrase would have crashed any 90s code generator.

The Maintenance Trap

But the leaky abstraction problem hasn’t disappeared. When the AI-generated code breaks, someone has to debug it. When security vulnerabilities emerge, someone has to patch them. When requirements change, someone has to decide whether to regenerate the module or surgically edit it. That someone needs to understand what the code actually does—not just what the spec said it should do.

This is the maintenance trap that keeps CTOs awake. If a spec generates 1,000 lines of code, you now own 1,000 lines of code. The technical debt doesn’t vanish because you didn’t type it yourself. The security vulnerabilities don’t excuse themselves because they came from a model.

Spec-driven development addresses this partially through synchronization. Kiro, for instance, keeps specs and code connected: developers can author code and ask the tool to update specs, or update specs to refresh tasks. This solves the common problem where documentation drifts from implementation. But it doesn’t solve the deeper question of how you refactor AI-generated code when requirements change. Do you regenerate everything and lose the human refinements? Do you surgically edit and let the spec drift? The tooling is still immature, and honest practitioners admit that the Day 2 operations story remains incomplete.

English Is Not the New Coding Language

Karpathy’s quip that “the hottest new programming language is English” makes for a great tweet, but let’s be serious for a minute. Writing a spec precise enough for an AI to implement correctly is still programming, just with different syntax.

The hard part of software development was never typing. It was identifying edge cases, handling failure modes, designing for scale, and anticipating how users will actually behave.

If a product manager writes a spec detailed enough that an AI can implement it without clarification, that product manager has essentially written logic. They’ve specified what happens when the user submits an empty form, what happens when the database times out, what happens when two users edit the same record simultaneously. That’s programming, whether or not it looks like code.

The better framing isn’t “anyone can code now.” It’s that AI forces engineers to become architects first. The value shifts from implementation to specification, from typing to thinking. This isn’t democratization; it’s elevation. The developers who thrive will be those who can decompose problems, anticipate failure modes, and communicate intent with precision—skills that were always important but are now existential.

The Security Question

We also worry about what happens when detailed technical designs flow into an LLM. A comprehensive spec for your core product is, in effect, a “god prompt” containing trade secrets, architectural decisions, and competitive advantages. Even enterprise-grade models raise questions about data handling, training pipelines, and access controls.

The emerging best practice is to keep the spec-to-code pipeline within controlled environments. Tools like Kiro run on AWS infrastructure with options for customer-managed encryption keys and controlled data usage. Organizations with stricter requirements are exploring private VPC-hosted models or retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) architectures that keep sensitive context local while leveraging cloud models for generation. The tooling is evolving, but the principle is clear: if your spec contains your competitive moat, treat it with the same security posture as your source code.

When Spec-Driven Development Fails

Spec-driven development isn’t a silver bullet. CTOs should watch for these anti-patterns:

The Infinite Refinement Loop.

Teams get trapped perfecting specs instead of shipping software. The spec becomes a procrastination device. If your team has spent three sprints refining requirements and generated zero working code, you’ve replaced one form of paralysis with another.

The Premature Precision Problem.

Some features shouldn’t be specified in detail upfront. Exploratory work, R&D projects, and early-stage prototypes benefit from vibe coding’s looseness. Forcing exhaustive specs on discovery work kills the discovery.

The Specification Theater.

Teams produce beautiful specs that look comprehensive but contain the same ambiguities in longer sentences. “The system shall handle errors gracefully” doesn’t become clearer by expanding it to three paragraphs of corporate prose. Precision requires thinking, not word count.

The Ownership Vacuum.

When AI generates the code and the spec lives in a shared document, accountability diffuses. Nobody feels responsible for understanding the implementation. Bugs become orphans. The fix is explicit ownership: someone’s name goes on every generated module, and that person is responsible for understanding what the AI produced.

The Regeneration Roulette.

Teams discover that regenerating a module from an updated spec produces subtly different code. Tests pass, but behavior changes in ways nobody anticipated. Version control becomes treacherous when the “source” is a spec and the code is an output.

The New Shape of Development

If I still have your attention then you are one of the few CTOs who knows that the reading of the methodology needs to evolve. The binary of Agile versus Waterfall is dissolving into something more nuanced.

The insight from spec-driven development is that front-loading thinking doesn’t mean returning to six-month requirements phases. It means investing in clarity before asking an AI to execute. The spec becomes the prompt. The better the spec, the better the output.

Thoughtworks describes this emerging practice as using “well-crafted software requirement specifications as prompts, aided by AI coding agents, to generate executable code.” The specification is more than a product requirements document. It includes technical constraints, architectural decisions, interface definitions, and acceptance criteria precise enough that an AI can validate its own work against them.

How the Workflow Separates

The workflow separates planning and implementation into distinct phases. During planning, you collaborate with the AI to understand requirements, identify edge cases, and document constraints. This is iterative work. The AI asks clarifying questions. You refine your thinking. The spec emerges from the conversation.

Once the spec is finalized, implementation becomes more mechanical—though never fully automatic. The AI generates code that conforms to the documented requirements. Tests verify behavior against acceptance criteria. Documentation stays synchronized because the spec is the source of truth, not a byproduct.

Kiro’s approach takes this further with what it calls “hooks”—event-driven automations that trigger agent actions when you save or create files. A hook might validate that every new React component follows the single responsibility principle. Another might ensure security best practices are enforced. These hooks encode team standards in a way that the AI can execute automatically, replacing the mental checklists that developers previously carried in their heads.

The Validation Stack

The tools for validating AI-generated code are maturing rapidly. SWE-bench tests models on real GitHub issues from popular repositories. Code review benchmarks measure whether AI tools catch meaningful bugs without overwhelming pull requests with noise. In one July 2025 evaluation by Greptile, leading AI review tools achieved bug-catch rates ranging from 6% to 82% on fifty real-world pull requests from production codebases. The variance is enormous, which means tool selection and configuration matter.

Evals—the systematic evaluation of AI outputs against defined criteria—are becoming a core competency. Teams are building pipelines that automatically measure functional correctness, code quality, performance, and security. The pass@k metric quantifies whether generated code passes all defined tests. Tools like SonarQube and Semgrep flag issues in readability and maintainability. Security audits detect vulnerabilities before they reach production.

The goal isn’t to eliminate human judgment. It’s to focus human judgment where it matters most: defining what the software should do, validating that it does it, and evolving the system as requirements change.

What To Do Monday Morning

If you’re leading an engineering organization, you don’t need to overhaul your entire methodology. You need to adapt your practices to match how AI tools actually work.

Start with a single team and a single feature. Before anyone writes a prompt, spend the time to write a proper spec. Include user stories with acceptance criteria. Document the technical design: data models, interfaces, dependencies. Break the work into discrete tasks. Be specific about edge cases and failure modes. If you find yourself writing “handle errors appropriately,” stop and specify what appropriate actually means.

Then hand that spec to your AI coding tool and observe what happens. You’ll likely find that the output quality improves dramatically. The AI will make fewer assumptions because you’ve made your intent explicit. Debugging will shift from “what did the AI think I wanted?” to “how do I refine what I actually want?”

Build Validation Into Your Workflow

If you’re generating code at scale, you need tests at scale. Define acceptance criteria that can be automatically verified. Run static analysis on every generated artifact. Treat AI-generated code with the same rigor you’d apply to code from a new hire: review it, understand it, and hold it accountable. The METR study found that developers who couldn’t explain what the AI had generated spent more time fixing problems than they saved in writing code.

Establish clear ownership for AI-generated modules. Someone needs to be responsible for understanding, maintaining, and securing that code. Don’t let the fact that no human typed it obscure the fact that humans are accountable for it.

Invest in Specification Skills

Invest in the spec-writing capability of your team. Product managers who can write precise requirements become force multipliers. Engineers who can translate ambiguous requests into unambiguous specifications become the new 10x developers. But be clear-eyed about what this means: spec-writing at this level is a technical skill, not a documentation chore.

Consider tools that enforce the spec-driven workflow. Kiro is one option. GitHub’s Copilot Workspace and Cursor’s agent mode offer similar capabilities. The common thread is structure: these tools separate thinking from typing, planning from implementing.

Address Security Upfront

Address security upfront. If your specs contain sensitive architectural details or trade secrets, ensure your AI tooling runs in controlled environments. Evaluate whether your compliance requirements allow cloud-hosted models or necessitate on-premise alternatives. Don’t discover your security posture after you’ve fed your product roadmap into a model.

Track the Outcomes

Track the outcomes. Measure time to first working implementation. Measure rework rates. Measure defect rates in production. Measure how long it takes to onboard a new developer to an AI-generated codebase versus a human-written one. If spec-driven development is working, you should see fewer iterations to reach a correct solution, less time spent debugging AI assumptions, and more consistent quality across the team.

The Battlefield Has Shifted

The methodology wars aren’t over. They’ve just shifted to a new battlefield. The CTO who recognizes that AI changes the calculus, who embraces detailed planning not as a return to waterfall but as a precondition for AI effectiveness, will build faster than competitors who are still vibe coding their way to production.

Royce was right in 1970: the risky approach is the one without iteration. He just couldn’t have imagined that the iteration would happen in a conversation with an AI, and that the output of that conversation would be a specification precise enough to generate working software.

The spec is the new prompt. Write it well and own what it produces.

Really nice post!! Which gives good posibilities for reflection :)

One of my main concerns with all of this is: where is the truth in the software we are building? The need for truth is IMHO not binary but exists on some kind of scale from "not important" to "very important". Is it the spec or the code, something in between, or a combination? I guess that the business domain of the software is what dictates this.

No matter how we turn this, it's even more important now than ever before that our teams are working towards the same goal, because if they aren't, the ambiguity of the goal is also amplified!

Fantastic thought provoking article. Was already doing many aspects of what you describe but am rethinking the overarching approach based on the observations.