The CTO’s Token Treasury

What every technology leader needs to know about the fundamental unit powering AI

In 1994, a computer scientist named Philip Gage published a short paper in The C Users Journal titled “A New Algorithm for Data Compression.” His technique, Byte Pair Encoding, was designed to shrink files by finding repeating patterns and replacing them with shorter codes. It was clever, efficient, and promptly forgotten by most of the industry for two decades.

Fast forward to 2016. Researchers at the University of Edinburgh were wrestling with a problem in neural machine translation: how do you handle rare words? Words like “antidisestablishmentarianism” or German compound nouns that stretch across half a page. Their solution? Dust off Gage’s compression algorithm and repurpose it for language. They published their findings, and within a few years, every major language model adopted some variant of this approach.

The same year that paper dropped, the ICO craze was building steam. By 2017, startups had raised over $5 billion through initial coin offerings. Tokens were everywhere. Bitcoin tokens. Ethereum tokens. Utility tokens. Security tokens. The word “token” became synonymous with speculative frenzy and blockchain gold rushes.

Now tokens are back. But these tokens have nothing to do with blockchain. They have everything to do with how AI reads, writes, and charges you for the privilege.

The global LLM market hit $6.33 billion in 2024 and is accelerating. Every API call, every ChatGPT conversation, every Claude response is measured and billed in tokens. Yet most CTOs I talk to have only a surface understanding of what a token actually is and why it matters for their technology strategy.

This is a problem.

The Invisible Tax on Your AI Budget

When OpenAI introduced GPT-4o mini, they priced it at $0.15 per million input tokens and $0.60 per million output tokens. Claude 3.5 Sonnet runs $3 per million input tokens. Gemini 2.5 Pro charges $1.25 per million input tokens for prompts under 200,000 tokens.

These numbers seem small until you realize what they mean in practice.

A token is not a word. A token is not a character. A token is a chunk of text that the model has learned to recognize as a meaningful unit. For English, that usually works out to about 4 characters or roughly 0.75 words per token. The sentence you’re reading right now? Probably 15-20 tokens.

But language is messy. And tokenization reveals just how messy.

Take the word “running.” In most tokenizers, that’s a single token. But “antidisestablishmentarianism”? That gets broken into five or six pieces. The tokenizer sees “ant” + “idis” + “establishment” + “arian” + “ism” and treats each piece as a separate billing unit.

Code and structured data behave differently. This is where CTOs building production systems should pay close attention. JSON structures, API responses, configuration files: all tokenized according to patterns the model learned during training. A 1,000-word English document might consume 1,300 tokens. The equivalent JSON payload could easily hit 2,000.

The UUID problem is particularly brutal. A typical UUID like a90d0d7d-9c5a-44de-8d3c-5b0da661de7c appears to be a simple identifier, yet it consumes roughly 23 tokens of processing capacity. A single enterprise prompt containing a dozen UUIDs can burn through 250+ tokens just on identifiers. Base64-encoded strings, long API keys, and dense log files create similar token explosions. For CTOs processing logs, handling database identifiers, or building systems that shuttle JSON between services, this adds up fast.

And then there’s the multilingual dimension.

Research from 2023 found that tokenizers trained primarily on English text created significant cost premiums for underrepresented languages. A sentence in Burmese or Tibetan might require ten times the tokens of its English equivalent. The good news: modern tokenizers are rapidly closing this gap. OpenAI’s o200k_base vocabulary—double the size of GPT-4’s tokenizer—has reduced premiums for major languages to roughly 1.5x to 4x compared to English. For CTOs building products that serve global audiences, this represents meaningful progress, though the gap hasn’t fully closed.

Inside the Token Factory

Understanding tokenization starts with understanding why we need it at all.

Language models don’t read text. They process numbers. Every word, every character, every emoji must be converted into a numerical representation before the model can work with it. The question is: what’s the right size for these numerical chunks?

Character-level tokenization treats each letter as a separate token. The word “hello” becomes five tokens: h, e, l, l, o. This approach handles any input you throw at it, including made-up words, typos, and foreign scripts. But it creates sequences that are absurdly long and loses the semantic grouping that makes language meaningful.

Word-level tokenization goes the other direction. Every word gets its own token. Great for common words. Disastrous for the vocabulary explosion problem. English alone has over 170,000 words in current use. Add technical jargon, proper nouns, and the infinite creativity of internet discourse, and you’re looking at a vocabulary that grows without bound. Any word the tokenizer hasn’t seen before? It simply cannot process it.

Subword tokenization splits the difference. The algorithms learn which character combinations appear frequently in the training data and group them into tokens. Common words like “the” or “running” get their own tokens. Rare words get broken into recognizable pieces.

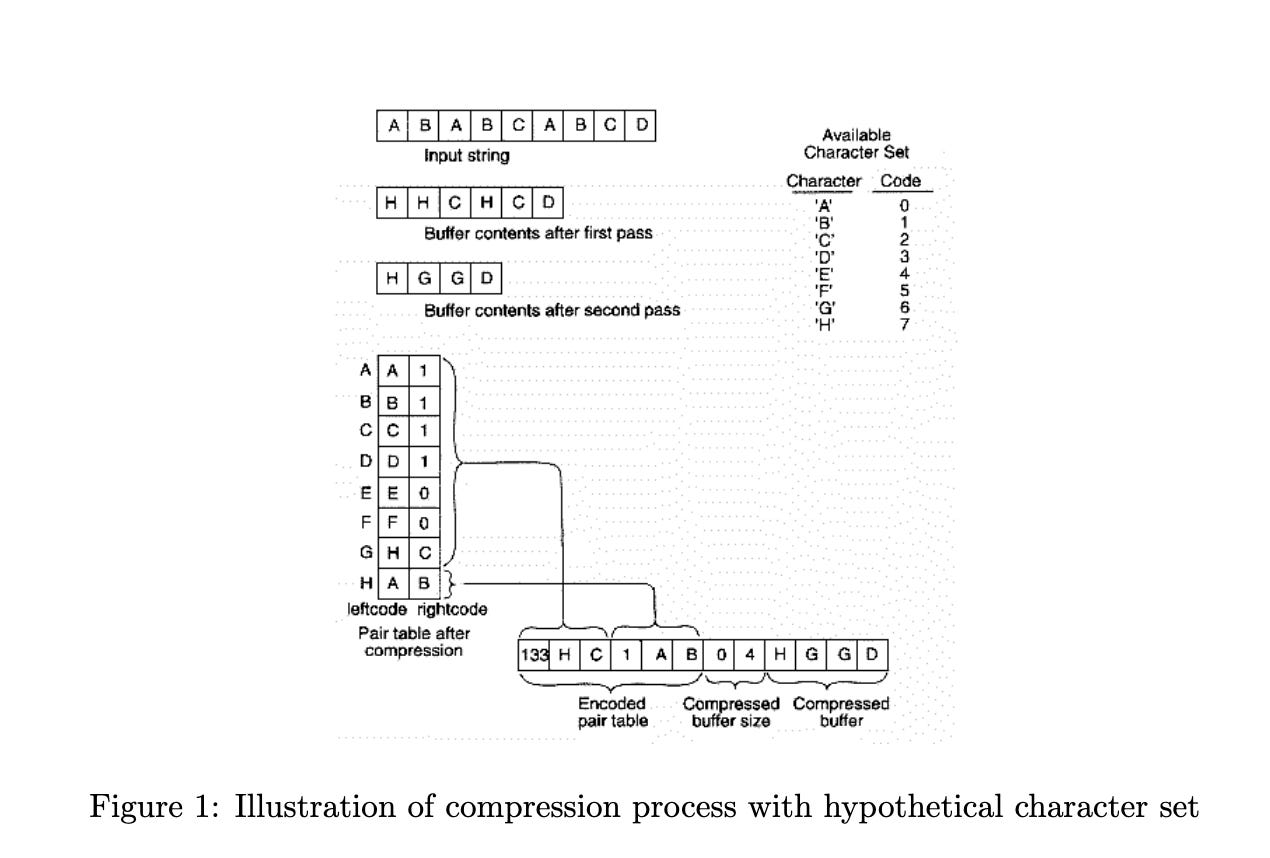

Philip Gage’s Byte Pair Encoding works by counting. Start with individual characters. Find the pair that appears most often in your training data. Merge that pair into a new token. Repeat until you hit your target vocabulary size.

GPT-2 used a vocabulary of about 50,000 tokens built this way. GPT-4 expanded to roughly 100,000. GPT-4o’s o200k_base tokenizer doubled that again to around 200,000 tokens—a major upgrade that dramatically improved efficiency for non-English languages and code. Each merge decision was made purely on frequency. No linguistic knowledge, no semantic analysis. Just counting.

This creates some interesting side effects.

Numbers are particularly chaotic. The number “12345” might tokenize as “123” + “45” in one model and “1” + “234” + “5” in another. This has implications for any application doing arithmetic or processing financial data.

Chinese characters often get tokenized one per token in older systems because they lack whitespace boundaries and weren’t as heavily represented in English-centric training data. The expanded vocabularies in modern tokenizers have helped here, but a Chinese user and an English user sending the same message still typically pay different rates because of decisions made during tokenizer training.

The Three Tokenization Families

Modern language models cluster around three main approaches:

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) powers the GPT family. Frequency-driven, merging common pairs until reaching target vocabulary size.

WordPiece (BERT, some Google models) considers likelihood rather than raw frequency, adding special prefixes to indicate word continuations.

SentencePiece emerged for truly multilingual models, treating input as raw bytes rather than assuming whitespace marks word boundaries.

The practical differences matter when choosing models for production. A tokenizer trained heavily on English will be cheap for English but expensive for other languages. A more balanced tokenizer costs more per token on English but delivers consistent pricing across languages.

What This Means for Your Architecture

Every technical decision in an LLM application traces back to tokens.

Context windows are measured in tokens. GPT-4 Turbo offers 128,000 tokens. Claude 3 handles 200,000. Gemini 2.5 Pro pushes to 1 million. But here’s the critical insight that many CTOs miss: filling those windows costs money, and the model’s ability to use information degrades for content buried in the middle of very long contexts.

Research published in Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics found that LLM performance is often highest when relevant information occurs at the beginning or end of the input context, and significantly degrades when models must access information in the middle, even for explicitly long-context models. Having a 2-million-token context window doesn’t mean your model will reason equally well across all 2 million tokens. Structure matters.

Prompt engineering is token engineering. A verbose instruction like “Please provide a comprehensive and detailed explanation of the following concept” consumes about 12 tokens. “Explain thoroughly” accomplishes the same goal in 3 tokens. At scale, that’s a 75% reduction in prompt overhead.

Caching strategies depend on tokenization and on prompt structure. OpenAI automatically caches prompts over 1,024 tokens, reducing costs for repeated requests by up to 50%. Anthropic requires explicit cache control headers. But caching only works when your prompts share an identical prefix.

Here’s a high-value tip: if your team puts a timestamp at the start of every prompt, you’re breaking the cache. Every single request gets processed from scratch because the prefix changes with each call. Move static content like system instructions, few-shot examples and reference materials to the beginning where caching can take effect. Dynamic content (user queries, timestamps, variable data) belongs at the end. Get this wrong, and you can burn thousands of dollars on requests that should have been cached.

Output costs consistently exceed input costs across all major providers. The ratio typically runs 3-5x, meaning that getting concise responses saves more money than optimizing prompts. Applications that generate verbose outputs pay a premium that accumulates fast.

The Emerging Alternatives

Here’s something worth tracking: tokenization itself may be a temporary architectural choice, not a permanent law of physics.

Research into token-free language models is advancing rapidly. Architectures like MambaByte and MEGABYTE learn directly from raw bytes, removing the inductive bias of subword tokenization entirely. These approaches show competitive performance with state-of-the-art subword Transformers on language modeling tasks while eliminating the entire vocabulary mismatch problem.

Why does this matter? Token-free models would end the multilingual cost premium entirely. A sentence in Burmese would cost exactly what a sentence in English costs—measured in bytes, not tokens. Code, structured data, and unusual text formats would all normalize.

We’re not there yet. These approaches face efficiency challenges that prevent immediate production deployment. But the research trajectory suggests that in three to five years, the entire token economy we’re building systems around today could look quite different.

For CTOs making architecture decisions now, the practical takeaway is to build systems that abstract away the tokenization layer where possible. Don’t hard-code assumptions about token costs into your economic models. Monitor your actual token usage by feature, by content type and/or by language so you can adapt as the landscape shifts.

Building Your Token Intelligence

Start by instrumenting your applications to track token usage at a granular level. Not just total tokens per day, but tokens per feature, per user segment, per content type. You need visibility into where your tokens go before you can optimize.

Test your content against multiple tokenizers. OpenAI provides a free tokenizer tool. Run your typical inputs through and compare the results against what you’d pay with Anthropic or Google. If you’re processing lots of code, compare tokenization efficiency across models designed for code versus general-purpose models.

Consider hybrid strategies. Simple queries might route to cheaper models with efficient tokenizers. Complex queries might justify premium models with larger context windows. The token economics should inform your model routing logic.

The Token Economy Evolves

The LLM API market shows aggressive price competition. Inference costs fell roughly 10x per year through 2024, with some analysts estimating that costs for GPT-3.5-class performance dropped 280-fold between 2020 and 2024. Prices for frontier models continue declining.

New tokenization methods continue to emerge. Research into morphologically-aware tokenizers promises better efficiency for agglutinative languages. Byte-level models that skip tokenization entirely are showing competitive results for some tasks. The field is far from settled.

What remains constant is the fundamental insight: tokens are the atomic unit of AI. Every capability, every cost, every limitation traces back to how text becomes numbers and numbers become text again.

Philip Gage probably didn’t imagine his compression algorithm would underpin a multi-billion dollar industry three decades later. But the principle he discovered holds: find the patterns, exploit the redundancy, and you can represent complex information efficiently.

For CTOs, the message is clear. Tokens aren’t just a billing unit. They’re the lens through which your AI applications see the world. Understand that lens, and you understand what your AI can and cannot do.

The blockchain tokens of 2017 were speculative instruments. The LLM tokens of 2025 are fundamental infrastructure. Both demand the CTO’s attention. Only one will shape the next decade of technology strategy.

Time to learn the currency.

This may be a framing gap, but I work with inference costs daily and don’t really see them trending downward in practice as models advance.

When you reference declining prices and a ~10×/year drop in inference cost, what layer of cost are you using? Token list prices, provider economics, or effective cost per task for users?

From an operational perspective, those seem to pull in different directions, especially as newer models require more reasoning and runtime. I’m interested in how you’re integrating that into your view.